Robert Hosea was by 1860 a man of substantial wealth, highly respected for his political acumen. He started in business as a steamboat clerk. He soon became a captain, then an owner, then a operator and manufacturer of steamboats. He built a substantial wholesale trade in Ohio and Mississippi River commerce.

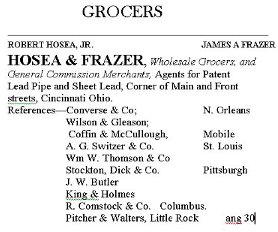

By 1845, when he had entered into a partnership with James Frazer, he was able to advertise as references an number of respectable firms in New Orleans, Mobile, Little Rock, St. Louis, Columbus and Pittsburgh.

Hosea's New Orleans reference, Converse & Co., was the firm of William Porter Converse, who conducted a large trading business in the Mississippi Valley, selling large quantities of cotton, sugar and molasses, among many other products, to northern merchants. Upon the establishment of the Bank of New Orleans in 1853, Converse was unanimously elected president by the other directors. By the time of the Civil War, Mr. Converse had retired to the North and began a trading business in New York, leaving management of the New Orleans firm in the hands of other family members and partners. William Seward had him arrested and imprisoned in Fort LaFayette for writing letters to friends at New Orleans. Lincoln ordered him released, along with California Senator Gwin and others, upon taking the loyalty oath.

By the 1850s, Hosea needed no references. His reputation was established. Other firms, such as Joseph Mogridge, a forwarding and commission house of St. Louis, Hutchins & Thompson, wholesale grocers of Cincinnati, and Gassaway Brashears & Co., auctioneer and commission merchants of Cincinnati, advertised him as a reference for themselves.

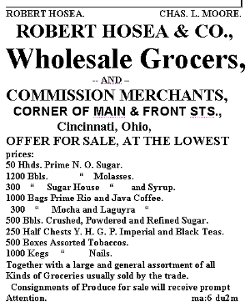

Hosea did a large wholesale business, advertising large numbers of hogsheads of sugar, barrels of rosin and molasses, kegs of butter, pigs of lead, Hyson, Gunpowder and Imperial teas and even cases of Steubenville jeans. His wife's brother Charles L. Moore, joined him in the business.

Immediately after John C. Fremont's defeat in the November 1856 eletions, Cincinnati area Republicans met to lament the election's outcome, celebrate their showing in the party's first national election and to plan for the next. They chose Hosea to preside at their meeting. Hosea ascended the podium to loud applause and gave an introductory address. Also present were Salmon P. Chase and Caleb Smith, both of whom would be members of Lincoln's cabinet after the next election.

Chase was Hosea's friend, neighbor and political beneficiary. At the next national election in 1860, Hosea worked the Chicago Convention trying to swing the nomination to Chase. Hosea soon recognized, however, that Chase could not be nominated. In addition, he realized that William Seward, the Republican front-runner, also could not be nominated. The nomination, Hosea believed, would go to either Cameron of Pennsylvania or Lincoln of Illinois. Two days before the nomination he informed Chase of his disappointing prediction.

Immediately after Lincoln received the nomination, Hosea wrote Chase giving him the news and Hosea's analysis of the causes of his defeat.

After Lincoln's election, Lincoln planned a train trip from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington, D.C., stopping at Cincinnati and other cities along the way. Hosea was named Chairman of the committee to welcome the President-elect to Cincinnati.

Sometime between the election and early February 1861, emissaries from seceded southern states approached Hosea to gain his cooperation in bringing Ohio into the southern confederacy. Because the Mississippi River trade was important to Ohio and to Hosea personally, southerners hoped that he could be persuaded to help bring Ohio into the confederacy once secession was irrevocably accomplished.

Hosea refused their solicitation and told them he would not cooperate in such a scheme and that, moreover, he would work against them.

Hosea knew that many Republicans did not understand the real reasons for southern secession. Accordingly, he resolved to send Lincoln a written brief outlining the elements of the "southern conspiracy."

Hosea was convinced that the southern slavery agitation was a political tool used to fire up the masses to bring about secession for tariff reasons. "I am in possession of information," he said, "which convinces me that the "slavery agitation" by the leaders of the southern secession movement, is but a mask to cover and hide from view for a time an ulterior purpose; nay more I have been solicited when the time comes to use my humble efforts in the agitation of the question for which the seceders are now preparing the way."

". . . the passions of the mob are excited by the constant theme and picture of northern aggression against slavery held up before them." "Thus in spite of intelligence of many in the south, and who should know better," explained Hosea, "the conspirators have seized the opportunity to 'fire the southern heart' as they express it, for such is the peculiar inflammatory nature of the "peculiar institution," that the slightest allusion to the danger of losing their slaves throws the mob into paroxysms of rage and fear. Their hate has been artfully directed against the population of the north who are now classed as abolitionists."

Hosea explained the real reasons for the slavery agitation. "The conspirators, he said, "have artfully brought about this condition of things to cloak and hide from view their ulterior objects." "[T]hey do not apprehend your administration doing any harm to slavery; but hate you as a whig of the old Henry Clay stamp, and fear a protective tariff more than they do aggression against slavery, . . .."

"Here lies the trouble," said Hosea, "and here the danger they apprehend from you; they are now in an agony of fear lest you appoint for your secretary of the Treasury a representative high tariff man from a state largely interested in Protection, such a man as Gen Cameron from such a state as Pennsylvania. The tariff question not "slavery" will be the dead point of danger in your administration."

Hosea reminded Lincoln what they all knew--that free trade had long been a favorite idea of the agricultural South and that the desire for free trade had been the cause of the nullification crisis in South Carolina. "Nullification was dropped," said Hosea, "but Calhoun and his disciples were industrious in spreading their ideas of Free trade, until now the conspirators acknowledge privately it is the only cause and object of secession; and by an unprecedented infamy make use of the fire brands of slavery to accomplish their purpose."

Hosea recounted the political events in South Carolina leading up to the 1860 presidential election. He identified by name some of the principal southern "conspirators." "Their dismay was great when the result of the election was known," he said. "The free trade conspirators up to the election had been so successful in their schemes, that they could scarcely realize that their own folly was mainly instrumental in elevating to the Presidential chair, the man, whom, last of all men, they would have preferred, one who was a regular old line Henry Clay Whig of the purest stamp." Hosea told Lincoln, "They attribute to you High protection proclivities, and hurl their hate and venom at you for this reason; not that they fear aggression against slavery, for they know that is impossible. It is not as a Republican that they oppose your election.

Although the brief quotations cited here convey well what was and was not the cause of secession, the reader should peruse carefully the whole document. It is by far the best contemporary description of the political mechanism that brought the war. Although the document has long been in Lincoln's papers that his son Robert donated to the Library of Congress, historians have completely omitted any mention of it.

Hosea signed the letter anonymously as "Buckeye." However, he offered Lincoln a way to learn who he was. "Should my name be required," he wrote, "you can have it, by expressing such a wish on your way from Indianapolis to Cincinnati, on which trip I will be among those to welcome you to this city."

Ask? Ask who?

Hosea knew that, as chairman of the welcoming committee, he would be at Lincoln's elbow during the many introductions on the train trip from Indianapolis to Cincinnati. Moreover, as chairman of the committee, he would be the one to whom Lincoln would logically address the question.

The two men did meet. Hosea gave the welcoming address to the President-elect in front of the gathered crowds at the train station. It was a brief address and an even shorter reply. Addressing Hosea, Lincoln thanked the citizens of Cincinnati for the reception and promised to speak more at length at the Burnet House Hotel.

If you were such a shrewd lawyer and politician as Lincoln, you would not have missed the opportunity to confirm the letter and press Hosea for any additional information.

There is some circumstantial evidence that Lincoln relied on Hosea's information. The next day after leaving Cincinnati, Lincoln spoke publicly of the slavery agitation in the South being an "artificial crisis" gotten up by "designing politicians," just as Hosea had explained. Lincoln had not used those words before his face-to-face meeting with Hosea.

Tragically, neither man fully understood the disastrous effects of the protective tariff on southern agricultural revenue.

For those who would like further confirmation of Buckeye's identity, see Robert Hosea's handwriting in his signed letter of February 14, 1857 to Cincinnati sculptor Hiram Powers then working in Italy. The letters from Hosea to Chase also provide handwriting corroboration.