There was no man more important to the organization of the anti-slavery crusade in America than Lewis Tappan. He was not alone, of course. There were many others with similar interests in limiting the political power of the southern slave owners. But Lewis stood head and shoulders above all others and he led the column.

He and his brother and business partner, Arthur Tappan, were the principal founders of the New York Anti-Slavery Society and of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Most of the famous names in the anti-slavery crusade took their initiative, their money and their direction from them.

There were business circumstances, however, that gave the Tappans a financial motive to embark upon an anti-slavery crusade with the purpose of limiting the political power of southern agriculture.

Lewis was first a Boston cloth merchant, selling imported fabric by the piece. Next, he became a cloth wholesaler, dealing in package quantities. Then he became a cloth manufacturer. He borrowed money from his brothers, bought stocks in cotton and woolen manufacturing companies and worked as managing agent for some of them.

Low-cost foreign competition, however, reduced his profits. At first, Lewis wanted no increase in the tariff, fearing that it would invite much more domestic competition. He soon changed his mind, however. Now, to stave off that foreign competition, he agitated for a protective tariff. Lewis led the agitation for the protective tariff. He did more than any other man in politically organizing the movement that culminated in the protective tariff of 1828.

Lewis was a prolific pro-tariff propagandist. He toiled long hours as a member of the Committee of Correspondence of the woolen manufacturers, writing tariff protection propaganda.

Lewis recognized that that their own representative, Daniel Webster, opposed a rise in the tariff rates. The influential Webster would be an obstacle to the desired tariff. Although the evidence is only circumstantial, it appears highly likely that Lewis seized an opportunity to convert Webster to protectionism.

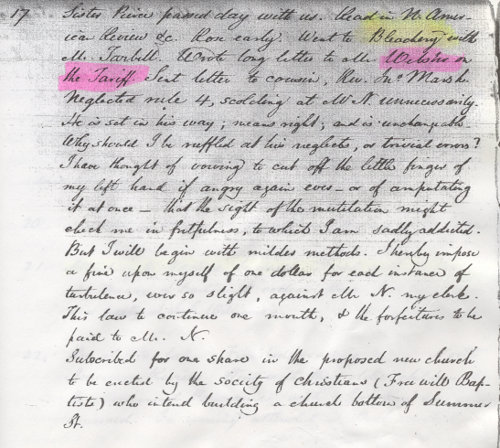

On January 14, 1824, Lewis Tappan wrote in his diary a simple one-line entry for the day:

"Making scheme for proprietors of Nashua Factory."

Lewis did not reveal even to his private diary what the "scheme" was about. A wealth of other circumstances, however, shows what they were about.

The Nashua factory was to be one of the largest textile manufacturing plants in New England. It would be formidable competition for Lewis' own Ware Manufacturing Company. Lewis had long feared an increase in the protective tariff for fear that it would stimulate an expansion of domestic manufacturing. Now that domestic expansion was a frightening reality, adding to the flood of textiles from Britain, Lewis saw a higher protective tariff as his only salvation.

As the plan for the Nashua company was initially proposed, Daniel Webster was to have been a subscriber for one fifth of the shares of the company. Webster's financial interest in a textile plant would have been very important to Lewis Tappan, because Webster could be very influential in shifting the balance in Congress on the protective tariff.

Three days later on January 17, Lewis wrote in his diary, "Wrote long letter to Mr. Webster on the Tariff."

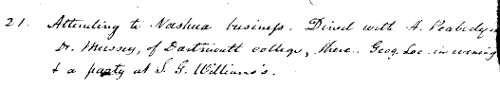

On January 21, Lewis recorded, "Attending to Nashua business. Dined with A. Peabody, esq."

Augustus Peabody was a Boston lawyer who was the largest single subscriber (75 shares or 25%) of Nashua stock. He held Daniel Webster's power of attorney to act for him with respect to the Nashua business.

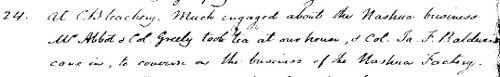

On January 24, Lewis wrote, "At CBleachery. Much engaged about the Nashua business. Mr. Abbot & Col. Greeley took tea at our house, & Col. Ja. F. Baldwin came in, to converse on the business of the Nashua Factory."

The Charlestown Bleachery was his fabric printing establishment at which he spent a great deal of time.

Daniel Abbott was a lawyer and a long-time friend of Daniel Webster. They hunted and fished together in law school and remained life-long friends. Abbott, who subscribed for 30 shares (10%), was the initiator and driving force behind the Nashua Manufacturing Company venture. Col. Joseph Greeley's firm, J.E. & A. Greeley, subscribed for thirty shares (10%) in the Nashua company. Col. James F. Baldwin was the superintendent of construction for the three-mile canal that supplied the water to power the mill.

In the following days, Lewis met with several men who, shortly after meeting with Lewis, purchased shares in the Nashua Company. Lewis himself took several shares. There were several transactions involving transfer by Daniel Webster to interested parties of shares for which he had subscribed but had not purchased.

The explanation for Lewis' "scheme" most probably lies in the fact that the company held shares in Daniel Webster's name as a subscriber, but did not give him the certificates. Webster, a notorious spendthrift, had no savings to invest. He did not pay for the shares for nearly a decade, all the while being credited with the dividends. He did finally pay for the shares when he sold them to the North American Insurance Company in December, 1833, after the Compromise Tariff of 1833 had set the tariff on a long decline over the next decade to a rate of twenty percent. The Nashua Company could look forward to ever-growing foreign competition. In 1833, the value of its stock was roughly half of the original par value.

Lewis' contribution probably included bringing in other shareholders to allow the company to support the arrangement for the impecunious Webster to retain an interest in manufacturing in order to sway his vote on the tariff, all the while maintaining "plausible deniability." Webster could always say, with a small shred of truth, "I do not own stock in the company." For nearly ten years, the treasurer issued perfunctory notices to Webster requesting payment. But no written reply from Webster appears in the Nashua records and the proprietors continued to keep the account open.

By scrambling to find other investors to replace the funds that Webster could not pay from his own pocket, Lewis could keep the project afloat, financing Webster's hidden interest. The other investors would have all been eager participants in the scheme because they, too, wanted a protective tariff.

If it was a bribe, it was an enormously effective one, for Webster did change his position on the tariff. In the vote on the 1828 "Tariff of Abominations," Webster voted for the tariff and brought with him other New England senators to pass the bill. That he did so is well known, at least among tariff historians.

The Woolen Bill of 1827, that Lewis had labored so hard to bring about, passed the House of Representatives and was brought up in the Senate where, with the quiet support of Daniel Webster, it came to a tie vote. Southern slave-owning cotton planter John C. Calhoun, then presiding over the Senate as Vice-President of the United States, broke the tie by his casting vote against the bill. This defeat by senators of the Slave Power sensitized Lewis and others in the North to the political power of southern agriculture.

The Senate vote on the bill shows the sectional nature of tariff sentiment. Only three free-state senators voted against the bill while 19 voted for it. Only one slave state senator voted for the bill. All the others voted against it. The cotton-state senators were unanimously against it.

The desperate Lewis Tappan, sliding toward personal bankruptcy, observed that the southern slave-state Congressmen were denying him and other northern manufacturers the tariff protection against foreigners to which they thought they were entitled. The vote made it abundantly clear that slave-state senators were his bitter political enemies.

The disappointed woolen tariff men regrouped to battle again for political dominance. They planned a national convention and held state conventions to select delegates. Here, Lewis was their foremost leader.

As chairman of the Committee of Arrangements for the Massachusetts tariff convention held in the Boston Hall of Representatives in June 1827, Lewis called the meeting to order and organized its business. He described the proceedings in his diary.

The hall was packed with hundreds of manufacturers and their representatives.  Lewis strode to the podium and called the meeting to order. He presided over the selection of the president of the meeting. Massachusetts Governor Levi Lincoln, Jr., was elected. After Governor Lincoln's brief address, Lewis again took the floor to present correspondence from prominent but absent pro-tariff activists. He then presented the principal business of the meeting which was to select delegates to the national tariff convention to be held in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania the next month. Afterwards, he participated in the debate.

Lewis strode to the podium and called the meeting to order. He presided over the selection of the president of the meeting. Massachusetts Governor Levi Lincoln, Jr., was elected. After Governor Lincoln's brief address, Lewis again took the floor to present correspondence from prominent but absent pro-tariff activists. He then presented the principal business of the meeting which was to select delegates to the national tariff convention to be held in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania the next month. Afterwards, he participated in the debate.

A major speaker at the event was former Massachusetts Senator Harrison Gray Otis, who had in 1820 voted against an increase in the tariff. Otis had since become an investor in the Taunton Manufacturing Company and now supported an increase in the tariff. Otis' letters to William Sullivan in 1820 gave instructions for implementing the secret northern conspiracy to use anti-slavery as a political tool to shift the balance of power. With Otis and Tappan together at the head of a northern tariff convention, circumstances were ideal for Lewis to learn from Otis, if he did not already know, the utility of an anti-slavery crusade to diminish the political power of the agricultural South

The national tariff convention was entirely Lewis's idea. He conceived of it and persuaded Matthew Carey and other protectionist minded men of Pennsylvania to hold the convention in their state.

Although a woolen manufacturer, Lewis owned an iron works. He knew first hand that the iron men desired tariff protection as well. A Pennsylvania convention would bring the iron and coal men into the movement. Other industries would be represented and a massive national log-rolling campaign would get under way to promote the protective tariff.

The 1828 tariff came too late to save Lewis Tappan's finances. His now unprofitable factory stocks, large debts, foreign competition and a business recession all combined to ruin him financially. He had to liquidate his assets and go to work to pay off his debts. His dream of being a "gentleman investor," returning home in the early afternoon to spend time in his home library, vanished. He went to work in his brother Arthur's silk wholesale firm in New York City where he soon felt "chained to the oar."

Lewis soon found another political cause to promote. The Tappan firm and other wholesale houses, the "regular merchants," were losing business and profits to the auction houses. The auction houses brought in shipments of manufactured goods from domestic or foreign factories and disposed of it by auction. These they advertised around the country in the large city newspapers to retail merchants who would travel to New York for the bidding. Just prior to the auction, bidders viewed the goods arranged in packages on the floor of the auction house. On auction day, fast-talking auctioneers ranged through the packages, hammering down the goods until they were all taken. When the auctions were over, the country merchants traveled home with their goods and the auctioneers went back to their office to plan the next auction.

Country merchants loved the lower prices and quick sales that conserved their time in the city, especially when the goods were available in convenient pre-packaged assortments.

The auctioneers had advantages over the wholesale stores of the regular merchants. They did not have the large cost overhead of the wholesale stores, including rent, heat clerks' salaries and merchant license taxes (although they did pay a small state duty). They had no need to maintain an expensive brick-and-mortar store building and fixtures, keep on hand a large inventory or hire year-round clerks to serve country merchants whenever they decided to come to New York. They needed only to place an occasional advertisement in the newspapers and employ a few workmen to move large packages of merchandise. They generally charged an auctioneer's commission of 2 ½% or 3 ½% of the price of the goods. The slim auctioneers' commission was far less than the 15% to 20% margin the Tappan store was accustomed to.

In an effort to stifle this low-cost economic competition, a group of New York merchants organized to seek legislation completely abolishing the business of auctioneering. Although Lewis was new in the city, he was already recognized as a talented political organizer. The New York men placed Lewis' name was first on the list of men assigned to write a constitution for the anti-auctioneering group. Lewis took an active part in the proceedings.

They published propaganda describing the auctioneers as a "moneyed aristocracy" that was "forcing" large quantities of "flimsy foreign fabrics" on the market at low prices, thereby "impairing integrity and destroying confidence in the ordinary course of mercantile transactions." The title of their sixteen propaganda pamphlet was entitled Reasons Why the System of Auctions Ought to be Abolished. Hezekiah Niles, the protectionist editor of the Niles Weekly Register published the whole text of the pamphlet in the columns of his paper.

The anti-auctions committee prepared petitions against the auctions and collected more than seventeen thousand signatures.

It was proposed in the House of Representatives to levy a tariff of 10% on the auction business. However, on May 1, 1828, the House failed to approve a resolution to even prepare a bill by a vote of 76 to 93 against. By themselves, northern legislators would have passed the bill, 63% in favor to 37% against. Southern legislators, however, opposed the tax and effectively killed it by their overwhelming opposition to it, voting 83% against the resolution. The "Slave Power" had stymied Lewis Tappan again.

On Tuesday evening, August 8, 1829, Lewis Tappan attended a large anti-auction meeting held at the Masonic Hall in New York City. Jeromus Johnson, who had just completed his second term in the U.S. House of Representatives presided. The meeting approved a memorial to Congress begging Congress to act to check the "ruinous abuse" of auctioneering "which if not checked, will destroy our mercantile character and prosperity." Lewis Tappan rose and gave "a striking speech on the present evils of auctions." He presented a series of resolutions the first of which said "That it is not our desire to abolish Auctions but to remove the enormous evils which make [the auctions] a a curse instead of a blessing to the community." The meeting adopted his resolutions unanimously.

Again, Lewis Tappan was not a mere participant, but he was a principal leader in another organized political campaign designed to employ the government as a tool to disable or impede his economic competition.

Now the two Tappan brothers joined the anti-slavery crusade that was already simmering in Boston. They set up William Lloyd Garrison in the newspaper business. Garrison became by far the most famous of the abolition newspaper editors. He had been cast into prison after a conviction for libel. The Tappans provided the funds to get him out of jail, gave him money to start an antislavery newspaper, The Liberator, and subscribed for a large number of copies. Garrison described Arthur Tappan as "the benefactor to whom I owe my liberation from the Baltimore prison in 1830; and but for whose interposition at that time, in all probability I should never have left that prison, except to be carried out to be buried."

The next instance in which southern Congressmen obstructed government help for the silk industry was the silk subsidy bill in 1832. Silk men in America believed there was an enormous waste of silk in the reeling process, as much as half the weight. They thought it was the result of imperfect reeling by persons who did not possess the requisite level of skill. Proper training of silk reelers, they thought, would give an enormous boost to the silk industry in the U.S. It might, they thought, do for the domestic silk industry what Eli Whitney's cotton gin had done for the cotton industry.

There was no silk reeling school in the United States. The silk men believed the federal government should help to provide a such a school. They sought a federal government subsidy to finance the training of persons in the U.S. to teach the art of reeling silk.

After three years of lobbying, a bill came up for debate on May 22, 1832. It provided for the payment of $40,000 to Peter S. Duponceau, a Philadelphia lawyer, for the benefit of Mr. John D'Homergue (pronounced "Domehrg"), an expert in silk reeling who had learned that art in his native France. The amount was to be applied to the purchase of equipment for instruction in reeling. It was to be a national school in which young men would learn to reel silk and prepare it for export. After graduation they would become directors of filatures, instructing the women who would actually do the reeling. It would, they thought, give a jump start to domestic silk production, making tens of millions of dollars for the country.

Duponceau published a pamphlet that was widely circulated saying, "We are among those who believe that the future success of the United States in the silk culture, manufacture and trade depends on the adoption of the plan proposed by Mr. Duponceau." The Duponceau and D'Homergue pamphlet, of which six thousand copies were printed for the use of Congress in 1828, contains numerous references to the "immense riches" and "great profits" that would flow to the United States if only the government would "encourage" the silk industry.

"The farmers' wives and daughters, when not engaged in feeding the worms," the silk men speculated, "were to reel the silk, and perhaps to spin and twist it, till silk should become as cheap as cotton, and every matron and maid rejoice in the possession of at least a dozen silk dresses."

Some northern congressmen favored the idea. Silk fiber was in several ways superior to cotton. Moreover, if it could displace cotton, it would weaken the economic and hence the political strength of the cotton South which had been so politically obstructive to the progressive development of northern industry. Because silk textiles were one of the largest import categories, congressmen were impressed with the large amount of wealth that would accumulate in the U.S.

On May 22, 1832, the bill came up for debate. Southern men opposed it. Representative James K. Polk of Tennessee moved to kill the bill by striking out its enacting clause.

Polk demanded to know where the proponents of the bill "would find the authority in the Constitution to give a donation of forty thousand dollars to this young foreigner, for the purpose of instructing sixty cadets, and twenty young women, of his own selection, in the art of reeling silk." "They might next be called on," he said, "to vote forty thousand dollars to instruct old ladies in the art of spinning flax; in fact," he argued, "they might be required to vote bounties for the pursuit or encouragement of any or every branch of industry. Perhaps it would be thought necessary next to vote thousands to set these young men in business after they should have learned the art from Mr. D'Homergue."

Polk concluded his remarks by pointing out that the representatives from Connecticut had testified that the art of reeling silk was already in successful operation in Connecticut without any protection or subsidy.

Polk's motion to kill the bill was voted down by a vote of 49 yeas to 68 nays and the House adjourned for the day. The southern effort to defeat the bill seemed weak and the prospects for its final passage still looked good.

When the House reassembled the next morning, however, the political mood turned dark. Massachusetts Representative John Quincy Adams presented the report of the Committee on Manufactures along with a bill concerning duties on imports. The tariff duties proposed in the bill were still very high. They were too high to suit the South. Now the stage was set for the bitter Nullification Crisis. The timing was unfortunate for the silk bill.

When debate on the silk bill resumed, the debate grew so heated, as Duponceau observed from the gallery, as "almost to threaten a dissolution of the Union."

Polk again moved to strike. It passed by a vote of 98 to 71 and this time the silk bill went down to defeat, mostly at the hands of the southern representatives of the "Slave Power and a few of their northern allies." Outrage over the tariff had turned the tide. If it had up up to northern Congressmen exclusively, the bill would have passed 61 to 39. Southerners, however, voted overwhelmingly against it, 58 to 10. Thus did the South nip in the bud the scheme of the silk men to get the subsidies they thought so important to their industry.

Now, the New York silk dealers would remain dependent on foreign supplies of silk. In the future higher tariffs might be laid on silk as a luxury good raising wholesale and retail silk prices, making silk more susceptible to replacement by ever cheaper cotton goods. It was a serious business worry and it undoubtedly preyed on the minds of the leading New York silk dealers such as Lewis and Arthur Tappan and John Rankin.

Prospects for the silk dealers were about to get much worse, however. The bitter debate on the tariff continued. Finally, in March, just before the end of the term of Congress, the Compromise Tariff of 1833 was enacted. A substantial number of northerners agreed to the compromise in order to avoid civil war.

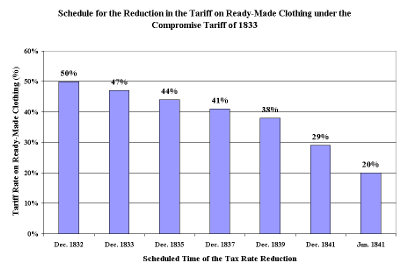

The Tappans and other fabric dealers were selling their products into the domestic market protected by a 50% tariff on imported ready-made clothing. If foreign ready-made clothing were allowed to come in at low tariff rates, cheap foreign goods with silk jackets, linings, lapels, cuffs and cravats already sewn would go directly to distributors and retailers, cutting out entirely not only the domestic fabric merchants but also their customers, the merchant tailors.

The chart below shows the rate at which the tariff on foreign ready-made clothing was scheduled to decline over the next nine years in accordance with the terms of the Compromise Tariff.

The fat monopoly of the domestic market was going to evaporate. Even worse, because there was no domestic production, any increase in the tariff on imported silk would further erode their competitive advantage over ready-made clothing from England, France, India and China. France, India and China clothiers had to pay no import tariffs on silk because they produced it in their own country.

Prospects for the future of the business looked gloomy. If only the southern "Slave Power" could be prevented from expanding westward into new states such as Texas where they would get new senators. It would take a massive propaganda campaign to demonize slavery to the extent that the nation would object to its westward expansion.

Before the end of that year, Lewis and Arthur Tappan, New York silk dealer John Rankin and William Green, Jr., the New Jersey and New York iron manufacturer and dealer, had formed the New York Anti-Slavery Society and the American Anti-Slavery Society.

William Green, Jr., had been a New York City dealer in iron. After the tariff of 1828, however, imported iron was prohibitively costly. Green, therefore, with British investors and boatloads of imported English skilled iron workers (put out of work by the U.S. tariff), built and operated the New Jersey Iron Manufacturing Company facilities at Boonton, New Jersey. Instead of bringing iron in over the tariff wall, they made an ironworks behind the tariff wall.

Now with the Compromise Tariff of 1833, however, they were in a real pickle. Their new ironworks were going to be exposed to superior British competition under low tariff rates. Like the silk men, they were facing desperate circumstances. It would bring big trouble for them financially toward the end of the decade.

They embarked on anti-slavery campaign with a vengeance. They hired agents to preach the gospel of anti-slavery throughout the North. They were called "The Seventy" after the seventy apostles of Christ mentioned in the Christian Bible. They printed and distributed anti-slavery pamphlets by the tens of thousands.

In the financial panic that began in 1837, the silk firm found itself unable to pay its bills as they became due. Competitors were taking away some of its customers. Tension rose between the brothers. Lewis looked around for other business opportunities and found opportunity in the credit reporting business. He began the Mercantile Agency, a firm that after many years and other managers became the modern credit reporting firm of Dun and Bradstreet.

One of the great objects of the anti-slavery crusade was to keep Texas from being annexed to the Union as a slave state. Lewis paid particular attention to the identity of Whigs who supported annexation. Since the credit reporting firms' customers included Whigs and Democrats as well as abolitionists as well as liberty party, Lewis' focus on anti-slavery politics caused problems with customers and friction with other members of the firm who lamented the lost business of alienated former customers.

Texas was annexed in 1845 by joint resolution just days before the inauguration of Democratic President James K. Polk. Texans formed a constitution and President Polk signed the documents admitting Texas on December 29, 1845.

A few months later in 1846, Congress passed a new tariff bill substantially lowering the tax rates. This tariff stayed in effect, with a slight further reduction in 1857, until after secession began in December 1860.

The lowered tariff passed the Senate by only one vote. Both new senators from Texas voted for the reduction. The South had regained the delicate balance of power and was understandably concerned about losing the advantage by its exclusion from newly admitted states.

There is yet another title to bestow on Lewis Tappan. He was the ultimate founder of the Republican Party. The honor is justified in this way.

Lewis founded and arranged financing for the National Era newspaper in Washington D. C. He hired Gamaliel Bailey to edit it.

Bailey's editorial hectoring of the anti-slavery Whigs and Democrats in the North to quick bickering, abandon the old parties and join up with the new anti-slavery Republican Party was the key factor of the formation of the Republican Party. For this role, Israel Washburn of Maine accorded him the title of the "immediate founder of the Republican Party."

There was no one in a better position to know the facts of the matter than Washburn. He presided at the meeting of dissident Congressmen the morning after the passage of the Nebraska Act. Bailey himself may have been present. Washburn himself proposed that the new party take the name "Republican" and that its platform should oppose the extension of slavery.

Although Washburn acknowledged that many others made important contributions, he said, "a work more difficult, if not more important, than theirs, remained to be accomplished-the practical work, the work of organization." "[T]he people who had been convinced of the wrong and danger of slavery," he explained, were members of different political parties. They must be extracted from the old parties and welded into a new organization that would oppose slavery extension. "The man who was to do this work, who was to combine and organize the scattered forces of anti-slavery opinion; in other words," he emphasized, "the immediate founder of the Republican party, was Dr. Bailey."

Bailey welded together into a political party those groups that resented the political power of the South. Southern control of the U.S. Congress had too long kept from their grasp the financial benefits they hoped to obtain by means of government.

"Dr. Bailey," Washburn wrote, had been the earliest, the ablest and the most influential advocate" of the organization of a new party, "in which all men who thought alike-on the vital question of the time, that of slavery extension,--should act together, . . .."

"Under the former methods of opposing slavery within the old parties," Washburn recounted, "controlled as they were by pro-slavery influences, no advance had been made." "It was to Dr. Bailey, more than any other man," wrote Washburn, "that the country was indebted for the simple but valuable instruction, how Slavery could be checked and Freedom saved." "The memory of this wise and good man," he said, "should be enshrined in the hearts of all Republicans. Congress should erect his monument in the Capitol."

The "Freedom" that Washburn referred to was not freedom for the slaves. They did not ask for that. They only wanted to hold slavery "in check." What they wanted was a perverse kind of "freedom" for northern tariff men to enact their economic legislation once they held the balance of power.

Lewis Tappan was a zealous seeker of advantages by means of government that the free market could not give. When democratic majorities stood in his way, he orchestrated political campaigns to demonize the opposition in order to swing the political balance in favor of the benefits he wanted that must come out of someone else's pocket. The anti-slavery crusade was nothing more than an effort to diminish the political power of the South so Lewis Tappan and his political allies could gain the balance and enact protective tariffs or other restrictive legislation. This was Lewis Tappan's modus operandi.