Raphael Semmes is famed for his command of the Confederate warships Sumter and Alabama that did more damage to northern shipping during the U.S. Civil War than any other in the Confederate Navy. His record is unsurpassed. He is unquestionably the most successful naval raider in all of maritime history.

After the war, Semmes wrote a book about his experiences: Service Afloat or the Remarkable Career of the Confederate Cruisers Sumter and Alabama during the War Between the States. In that book, he told of his meeting with a British naval officer, the Captain of HMS Cadmus lying at anchor in the harbor at Trinidad in August 1862.

To the surprise of the British captain, who thought it could not last long, Semmes predicted a long and bloody war. The tariff, not slavery, he explained, was the cause of the war. The slavery issue, he explained, was merely an instrument dishonestly used by the northerners to gain political power for tariff purposes.

Semmes was precisely correct. He was in a unique position to know the whole truth of it.

How he came understand the effects of the tariff and the ulterior motives of the anti-slavery crusaders requires some knowledge of his family connection, his early legal experience in court with the anti-slavery men, his familiarity with principles of of political economy, his work for the Confederate government and his high level of command in both the Confederate Navy and Army which required his personal communication with Confederate leaders at the highest level, including President Jefferson Davis.

The Early Years

Semmes was born in 1809 to a Maryland tobacco farmer, Richard Thompson Semmes, and his wife, Catherine Middleton. Catherine was the daughter of South Carolina lawyer and planter Arthur Middleton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. She died, however, when young Raphael was two years of age and his father died when he was ten. He was taken in and cared for by his uncles. He lived at his Uncle Raphael's Georgetown home.

His Uncle Raphael had, in his younger days, sailed to many ports around the world working for a maritime trading company. Settling down in Georgetown, the senior Raphael became a successful businessman, operating a wholesale grocery business, Semmes and Company. In addition, he was a bank director, an insurance commissioner and a tavern-keeper.

Uncle Alexander Semmes owned a fleet of merchant ships but was lost at sea sometime in 1826 or 1827.

Another uncle, Benedict Joseph Semmes, was a medical doctor who served in the Maryland state legislature and in 1825 presided as speaker in the House of Delegates. In 1828, he was elected to the U.S. Congress and served from 1829 to 1833. He enabled the young Raphael to gain an appointment as a midshipman, that is, an officer-trainee, in the Navy.

Benedict was in Congress during the tumultuous years of tariff controversy in the Nullification Crisis and the debates on the Compromise Tariff of 1833. He spoke on the floor of Congress on particular aspects of the tariff bills. He was in an excellent position to give the young Raphael an insider's view of tariff politics.

Semmes was appointed a midshipman in the navy in 1826. He served aboard naval vessels USS Lexington, Erice and Brandywine and sailed to the Mediterranean and to the Caribbean. In 1831, he attended the Navy School at Norfolk, Virginia. After finishing second in his class, he was commissioned a "passed midshipman" in 1832.

For several years, the Navy had more officers than it could use in peacetime. Consequently, it put many officers, including Semmes, on long unpaid leaves. Semmes used the time to read for the bar in his brother Samuel's law office. He was admitted to practice before the Maryland Bar in 1834 or 1835.

Cincinnati and the Spencers

In 1834, Raphael traveled to Cincinnati and lived there for several years, engaged in the practice of law. He boarded at the home of Oliver and Electra Spencer. Oliver Spencer was a businessman and Methodist clergyman, who had served as president of Ohio's first Banking institution.

While boarding with the Spencers, Semmes fell in love with their daughter Anne Elizabeth and married her in 1837. Anne and Raphael had six children, all of whom survived into the next century.

At least two of Spencer's sons became prominent in Cincinnati. Anne's brother Henry E. Spencer, a lawyer, served as mayor of Cincinnati for four consecutive terms from 1843 to 1851. He was regarded as "a man of great integrity, fine abilities and highly spirited." During his mayoral terms he was a member of the Whig party, but held the office, it was said, "to the satisfaction of all parties."

Henry later switched his allegiance from the Whig to the Democratic Party. He served for many years as president of the Fireman's Insurance Company, a prosperous Cincinnati firm.

Henry's brother Oliver M. Spencer, Jr., was a member of the law firm of Spencer and Corwine and served as judge of Superior Court from 1854 to 1861. Oliver's partner Richard M. Corwine later became an active Republican and corresponded with Abraham Lincoln on political matters.

The Spencer family connections undoubtedly gave Semmes a wealth of information on Cincinnati citizens, their business and politics. While Semmes was there, both brothers boarded at their father's home. Dinner table conversations in the Spencer household were especially likely to have given Semmes a wealth of wisdom and information on Cincinnati affairs.

Semmes vs. Salmon P. Chase and the Abolitionists

As a practicing lawyer, Semmes took on a case in which he defended men who had been sued by the Cincinnati anti-slavery men.

Lewis Tappan, a New York silk merchant, was the nation's foremost pro-tariff organizer and leading anti-slavery agitator. In 1835, Lewis and his brother Arthur had extended their campaign in Cincinnati. They had sent Lyman Beecher to Cincinnati and guaranteed his salary as President of Lane Seminary in the belief that he would emphasize antislavery doctrines in teaching the students. They subsidized Theodore Weld and others from the Oneida Academy and sent them to the Lane Seminary.

They and the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society subsidized James G. Birney in setting up near Cincinnati an antislavery newspaper, The Philanthropist. Birney published his first issues in January, 1836. He had the paper printed in the Cincinnati print shop of Achilles Pugh.

Southerners grew outraged at the nearby propaganda machine that threatened their slave property and aimed to ultimately limit their political power in the Senate by preventing westward expansion to new territories. They threatened to boycott Cincinnati products.

A large group of Cincinnati citizens led by prominent merchants and bankers grew frightened that a threatened southern boycott of commerce with Cincinnati would ruin the local economy and bankrupt their businesses and banking institutions. Oliver M. Spencer, Sr., Semmes' father-in-law, was a member of the committee of gentlemen who met with the abolitionists and demanded that they cease publication of the troublesome paper.

The executive committee of the Anti-Slavery Society refused their demand.

Spencer and twelve others signed a resolution announcing the failure of negotiations and recommended action against the abolitionist press.

At midnight in mid-July, 1836, an anti-abolitionist mob broke into Pugh's workplace, broke his printing press and destroyed the current weeks' issue. Undeterred, Pugh obtained a new printing press and was soon printing the paper again.

Again, at the end of July, the mob broke into Pugh's print shop, threw the parts of the press and the type and type cases into the street and prepared to burn them. The Cincinnati mayor, however, mounted the pile and dissuaded the crowd from setting fire for fear the conflagration would spread to nearby houses. The crowd then dragged the dismantled press down the street and threw it into the Ohio River.

Pugh then moved his printing operation to Springboro, Ohio, about thirty-five miles north-north-east of Cincinnati, and shipped the printed issues down to Cincinnati on the canal.

The abolitionists hired Salmon P. Chase and other lawyers who brought suit against some members of the mob to recover damages for the destruction of the press. Two decades later, Chase's election as governor of Ohio was a signal to other northern tariff men that anti-slavery could be the effective basis of a political coalition. The event gave impetus to the founding of the Republican political party. Although Chase had been his rival for the nomination, Abraham Lincoln appointed him as his Secretary of the Treasury.

Raphael Semmes, along with other lawyers, represented the defendants. At the trial, Semmes went head-to-head against Chase and the other lawyers for the abolitionists.

In an article published in The Philanthropist after the trial, the editor accused Semmes and the other lawyers of falsely representing the abolitionists:

Messrs. Semmes, Reed and Fox endeavored with great ingenuity to operate on the prejudices of the Jury, by exaggerated, distorted and false representations of the doctrines, measures and designs of abolitionists. We felt no otherwise concerned about this, than as it betrayed lamentable ignorance or prejudice; for so gross were their caricatures, we knew that no reflecting mind could be imposed upon by them. The speech of Salmon P. Chase was well calculated to correct the impressions, which the gentlemen just named, labored so ingeniously to produce.

Mr. Chase, after an earnest vindication of the character of abolitionists, and reading from the work of Dr. Channing on Slavery, proceeded in a perspicuous, able and honest way to comment on the evidence.

The arguments of Semmes and the other lawyers for the defense, however, must have had an effect. The jury awarded only $50. Birney himself reported that "disinterested spectators scarcely thought a verdict would be returned for less than two hundred and fifty dollars." The low verdict was a surprise. The full article is here.

Any court records of the trial that may have existed were likely destroyed in the courthouse fire years later. We don't know exactly what were Semmes' "representations of the doctrines, measures and designs of the abolitionists" that the editor of The Philanthropist complained about. However, some circumstances suggest what they might have been.

The occupations of the men on the executive committee of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society suggest the motives that Semmes and the other lawyers for the defense undoubtedly suspected. The members were James C. Ludlow, Isaac Colby, Wm. Donaldson, James G. Birney, Thos. Maylin, John Melendy, C. Donaldson, Gamal. Bailey, Rees E. Price, Augustus Wattles and William Holyoke.

These men had substantial financial interests in the manufacturing of tariff-protected goods. Congressmen of the Slave Power had forced a reduction in the Tariff in 1833 to resolve the crisis of South Carolina's nullification of the tariff. Having benefited for several years by a high protective tariff, they were becoming desperate as the tariff rate on foreign goods was reduced every two years by the schedule of the Compromise tariff, making it easier for foreign goods to invade their market. They faced the very real possibility of severe financial distress.

They already knew from the days of the Missouri Controversy of the scheme to agitate against slavery to politically obstruct the westward march of southern agriculture so as to shift the balance of power on the tariff. There was a very large amount of money at stake. Anti-slavery agitation was a very practical strategy to limit the political power of tariff-obstructing southern agriculture. Now the scheduled reductions of the 1833 tariff energized them again to political action.

The Carriage Manufacturers

James C. Ludlow was the chairman of the executive committee. He was the son of Israel Ludlow, Cincinnati's founder who originally laid out the town. James owned industrial property on Mill Brook in Cincinnati, including at least two mill seats, that is, property adjacent to a waterfall suitable to power a factory. In his will of March 19, 1841 he directed that the mill properties "be retained in the family for the term of ten years at least, that their true value may be the better appreciated."

The political context tells why. Earlier that month, a Whig president had been inaugurated. Ludlow was undoubtedly hopeful that the Whig Congress would pass protective tariff legislation, giving "encouragement" to domestic manufacturing, thereby increasing the usefulness and value of the Mill Brook properties.

Ludlow had yet another concern for the prosperity of Cincinnati manufacturing. In 1815, a family relation, Mary Ludlow, married George Miller at about the time he began manufacturing carriages in Cincinnati. The carriage firm later became George C. Miller Sons Carriage Company, a large scale manufacturer of carriages, carriage parts and iron and steel agricultural implements. Mary died in 1837 and George remarried. James, in his will, left substantial property to George Miller in trust for Mary's children, whose descendant ultimately carried on the business into the next century.

William Holyoke, another member of the executive committee, is described in the Cincinnati directory as a "coach maker, E s Syc[amore]. b[etween] 3d and 4th.". A history of the Cincinnati vehicle industry reports that "on Sycamore Street, between Third and Fourth Streets there was in operation a carriage factory known as the Holyoke Carriage Shop, owned by Henry Villatte, building a great variety of work, such as coaches, phaetons, gigs and other pleasure carriages, and also wagons, carts, drays, etc."

Carriages and carriage parts were the frequent subject of tariffs. Raphael's Uncle Benedict Semmes, while in Congress, had voted on June 22, 1832, to increase the tariff on "carriages and parts of carriages" from twenty-five percent to thirty percent.

Now, the Compromise Tariff of 1833 was gradually reducing the tariff rate on carriage parts to twenty percent. That would better enable the British iron industry to supply competing carriage parts. The Ohio carriage manufacturers certainly would have had resented the "Slave Power" for compelling a reduction in the tariff rate, especially when they were being encouraged by the constant drumbeat of tariff protection propaganda by the Niles' Weekly Register and other newspapers that followed its lead.

The Cincinnati Ready-Made Clothing Industry

Some of the members of the executive committee were interested in the Cincinnati ready-made clothing industry which was strongly affected by the protective tariff. They were Isaac Colby, William Donaldson and Christian Donaldson.

In the 1830s, Cincinnati was already becoming the great western manufacturing center for ready-made clothing. As New York City, Boston and Philadelphia served the east coast, Cincinnati served the West, including communities up and down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

By 1841, Cincinnati had 86 "clothing stores," with 813 "hands," and 25 hat factories with 181 hands. In addition, "nearly four thousand females" sewed garments in their own homes for the clothing stores.

By 1851, there were 108 stores and shops employing 950 hands in the shops and supported by more than nine thousand women working in their homes. There were forty hat factories employing 367 hands. William H. Carver's hat-block factory specialized in making the forms for manufacturing and displaying hats.

The Cincinnati industry grew rapidly because of the high costs for western merchants to travel to the eastern seaboard cities of New York and Philadelphia to buy their fabric and clothing as they had done in earlier years. A trip to New York could take weeks-Cincinnati only a few days.

Like the tailors in Philadelphia, New York and Boston, however, the tailors of Cincinnati also faced the threat of foreign competition. Cheap foreign imports, they believed, threatened their business.

In 1828, the tailors had grown alarmed at the provisions of the pending tariff bill that, they said, "appears to threaten the existence of their business, and to annihilate the hopes of subsistence of many thousand persons who are employed and supported by the trade." Philadelphia tailors begged Congress to protect them by raising the tariff rates on imported ready-made clothing. They were afraid that the cloths and ribbons they bought would cost more because of tariff protection on woven fabrics. They would be ruinously squeezed between higher fabric costs and cheap, ready-made clothing imports.

At the previous revision of the tariff, the duty on ready-made clothing was left unchanged at 30% while the duty on imported fabrics was increased to 33 1/3%. It abolished the protection to the domestic manufacturer, they said. "[T]hey submitted without complaint," they reminded Congress, "confiding in the wisdom of the Government." "Nothing but impending ruin," they said, "now urges them to this remonstrance."

They thought no one in Congress had perceived the pernicious effect the pending tariff revision would have on them. "They are slow to believe," they said, "that Congress, in violation of the principle of the bill, would willingly destroy a branch of domestic industry indispensable to civilization, which stands in the way of none, which gives employment to decrepitude, otherwise helpless, and support to indigent females, by one of the few trades in which they can be suitably employed, to drain the country of money to nourish and support that foreign skill and industry which they are struggling to rival, and all this at the expense of a most serious diminution of the revenue."

If the duty on fabrics was raised, and the duty on clothing kept the same, then the fabrics would arrive in the form of finished clothing. Half of the capital used to import fabrics, they believed, would now turn to import ready-made clothing instead.

The price savings would be so great that domestic industry could not compete, even if they worked for free. It would, they said, "operate as a bounty on foreign industry," and "soon open a [foreign] trade in ready-made clothing to an extent never before thought of."

Boston tailors also begged Congress for changes in the tariff bill. The bill then pending, they insisted, "would be of destructive consequence to their business and give to other branches of industry a partial and disproportionate encouragement." Their business, they said, afforded "an honest and respectable support to a very large number of their fellow-citizens." They were "not only threatened with serious injury, but with entire ruin." If the tariff bill as proposed were passed, they would be "immediately ruined." "[F]oreign interests," they predicted, "would be advanced and foreign artists encouraged and enriched."

"Individuals," they complained, "are allowed to import, with themselves, their clothing free from duty." "[I]t is well known," they asserted, "that individuals coming from abroad are in the habit of bringing with them, as their own clothing, clothes for others, which are admitted free from duty; which operates both to defraud the public revenue, and prejudice the American artists."

Judging from the language employed, the Boston and Philadelphia tailors were seriously frightened by the possibility of diminished tariff protection. Congress, however, did raise the tariff on ready-made clothing. The tariff of 1828, called by many the "Tariff of Abominations," passed Congress and became law. Many in both the North and South were unhappy with it.

The following chart shows the vote in the Senate on increasing the duty on ready-made clothing. Observe the solid array of southern slave-state senators lined up against the increase.

Senate Vote to Insert "on clothing ready made, fifty per centum ad valorem," May 5, 1828

Passed by a Vote of 25 to 21

84% of free-state senators voted in favor of the increase and 78% of slave-state senators voted against it.

Although the ready-made clothiers got their higher tariff rate, it was by a slim margin of only four votes. The slave state senators were nearly unanimous against them. The three southern votes in favor of the tariff increase (Barton, Bouligny and Eaton) were from states where the balance of political power might easily swing the other way.

Barton of Missouri, running as an anti-Jacksonian, was defeated by Alexander Buckner at the next election in 1830. Buckner, although a Jacksonian, voted for an increase in the tariff on ready-made and voted against the Compromise Tariff of 1833 that set all tariff rates on a long decline to 20%.

Bouligny of Louisiana left the Senate in 1829 and was replaced by Edward Livingston who, shortly thereafter, became President Andrew Jackson's Secretary of State. His replacement, George Waggaman, although a tariff-loving sugar planter, voted against the increase in the duty on ready-made in 1832 and for the tariff reduction of 1833.

Eaton's vote is a puzzle. He left the Senate in 1829, however, to serve as Andrew Jackson's Secretary of War. His replacement, Felix Grundy, voted for the increase in ready-made in 1832 but voted for the tariff reduction of 1833.

The ready-made clothing manufacturers had only a weak hold on their tariff advantage. It hung by a slender thread. In the minds of the ready-made manufacturers and their vendors, southern power over the tariff hung over their heads like a fearsome Sword of Damocles.

In 1832, Congress prepared another tariff revision. The wool men and the ready-made clothing men wanted an increase in the tariff rate from 50% to 57%.

The Senate voted July 6, 1832 on the proposed amendment to increase the tariff rate on wool and ready-made clothing. The amendment passed 25 to 23.

It began to look like the ready-made clothing men might actually get their increase. It was not to be, however.

The House voted on July 10, 1832 to reject the proposed Senate amendment by a vote of 90 to 84. The slave-state men voted 80% against the increase.

The hopes of the ready-made clothing men were dashed on rocks of southern resistance.

The tariff bill, without that increase, passed both houses of Congress and became law. The rates were still too high for the South, however. South Carolina passed an ordinance nullifying the tariff law. President Jackson, however, would have none of it. He threatened to hang the perpetrators. Both sides prepared for armed conflict.

Congress warded off the crisis by means of the Compromise Tariff of 1833 that set the tariff rate on a long decline over nine years. That law declared that tariff rates in excess of twenty percent would be reduced. Since the tariff rate on ready-made clothing was then 50%, the excess over 20% was 30%. The reduction would be one-tenth of that excess every two years. One-tenth of 30% is 3%. The tariff rate would drop from 50% on the following schedule:

After December 31, 1833, to 47%.

After December 31, 1835, to 44%.

After December 31, 1837, to 41%.

After December 31, 1839, to 38%.

After December 31, 1841, to 29%.

After June 30, 1842, to 20%.

For the ready-made clothing manufacturers and their vendors who had been fighting for an increase in the rate from 50% to 57%, the reduction from 50% to 20% was an awful defeat. They perceived it to be their economic doom. They saw the slave-state congressmen as the cause of it.

Lewis Tappan, the nation's largest silk dealer, for whom the Cincinnati ready-made manufacturers were important customers, understood that the reduction in the tariff rate would enable foreign ready-made manufacturers to increase their share of the American market. Foreign manufacturers would buy from foreign silk dealers the silks for their ready-made clothing, reducing the Tappan's share of the market. No longer would he and his fellow New York silk merchants sell so many silk ribbons and gros de Naples to Cincinnatians.

Clothes made in France, England, Germany and Italy, with silk linings, lapels, cuffs and cords already sewn, would come in under the low 20% tariff. Foreign silk dealers would then get the sales that Lewis and Arthur Tappan wanted for themselves. Foreign tailors and their seamstresses would get the work that the Cincinnati tailors and seamstresses now had. Foreign manufacturers and dealers in scissors, knives and irons would profit instead of Cincinnati men.

The slaveowners of the South, however, looked forward eagerly to lowered tariff rates and the higher cotton revenues they would receive. Refer again to the relationship between cotton prices and tariff rates. High tariff rates mean devastatingly low cotton prices.

This opposite relation with respect to taxation was the mechanism driving the Cincinnati garment manufacturers' hatred of the slaveowners. The slaveowners felt it in their bones that the high tariff, for its devastating effect on cotton prices, was their economic doom. The Cincinnatians, having been taught the gospel of the American System by Henry Clay, Hezekiah Niles and others, believed that tariff protection was their birthright. They came to regard the slave-state congressmen as the army of a backward, non-progressive society that was at war with their best interests, retarding their progress in the Union.

Lewis Tappan was a practical man. He realized that if southern agriculture were to expand into the western territory, the new states formed out of that territory would probably also oppose the tariff. Their congressmen would be added to the balance of voting power in Congress, swaying the beam inexorably to favor of the southern interest. The domestic manufacturers would be "locked-out" from tariff protection for the foreseeable future.

There was, however, one way southern agriculture might be kept from expanding into the new territories. The southern agricultural labor force consisted to a large extent of Negro slaves. It was a great political vulnerability. If slavery could be prohibited in the territories, slaveowners would not go there.

Probably, Lewis already knew of the scheme of the Boston Federalists, hatched by Harrison Gray Otis, William Sullivan and other political associates to advance the antislavery crusade of James Tallmadge, Jr. and Rufus King as a means to "take the scepter" of national power from the South. The North had lost the battle to keep slavery from Missouri. Texas would be next.

Lewis realized that a concerted national campaign against slavery might sway public opinion in the North so that the expansion of slavery could be stopped. Lewis was by then an old hand at political organizing for legislation to restrict his economic competition. He had organized the national campaign in 1824-27 for tariff protection against imported wool and woolen fabrics. He played a leading role in organizing the campaign in 1828 to abolish the profession of auctioneering-his low-priced competitors in the distribution of silk goods.

By now, Lewis knew just what to do. He set up anti-slavery societies in Boston, New York and Philadelphia, the east-coast centers for ready-made clothing manufacturing. Next, he turned his attention to Cincinnati, then becoming the western center of ready-made clothing manufacture.

Isaac Colby was a physician. His tariff interest isn't immediately obvious. However, young Isaac Colby and Samuel Colby were tailors. Sarah Colby ran a millinery business in nearby Batavia and may have been a manufacturer of ladies hats. They were a part of the the great Cincinnati ready-made clothing business.

The Donaldson family patriarch was an immigrant who for a time operated a textile mill across the river from Cincinnati. His sons took to the clothing business naturally. The whole family was heavily dependent on the clothing industry in Cincinnati.

Alexander Donaldson was a "finisher." "Finishing" is a general term that applies to a variety of textile finishing operations performed after weaving the cloth, such as de-sizing, scouring, bleaching, calendering, dyeing and printing.

Christian Donaldson was the principal proprietor of C. Donaldson & Co hardware dealer firm at 18 Main Street. Francis Donaldson and George Donaldson worked at the firm. They supplied cutlery, including scissors, knives, button-hooks, stilettos, bodkins, hooks and eyes, irons, and other similar hardware, to this industry as well as to other local manufacturing industries.

Christian Donaldson was the principal proprietor of C. Donaldson & Co hardware dealer firm at 18 Main Street. Francis Donaldson and George Donaldson worked at the firm. They supplied cutlery, including scissors, knives, button-hooks, stilettos, bodkins, hooks and eyes, irons, and other similar hardware, to this industry as well as to other local manufacturing industries.

Each of the thousands of Cincinnati seamstresses would require for her workbasket several pairs of scissors: common scissors, linen shears, rounded-point scissors, sharp-point scissors, flat-knobbed lace scissors, button-hole scissors. For the steady worker, duplicates might be required while the dull pairs waited re-sharpening.

James Donaldson and Thomas Donaldson were tailors, doing business at Front Street, while tailor William Donaldson did business at Gano Street between Main and Walnut.

The Teachers

Thomas Maylin and Augustus Wattles were teachers. Maylin was an English immigrant and a member of the Congregational Church along with the Donaldsons. Wattles had been recruited by his fellow classmate at the Oneida Institute, Theodore Dwight Weld, to attend the Lane Seminary in Cincinnati. At the Lane Seminary he became involved with Weld in anti-slavery activities. He superintended a school for Negroes. In 1836, he became an official agent and fund raiser for Lewis Tappan's American Anti-Slavery Society. In later years he would become a friend of John Brown. Wattles harbored Brown in his home the night after Brown murdered a Missouri slave owner and took his slaves. Wattles reprimanded Brown for violating the peace but nevertheless sheltered him.

Maylin and Wattles were both members of The Western Literary Institute and College of Professional Teachers. "The College of Teachers," as the organization was popularly called, was a private propaganda organization devoted to raising the public consciousness of the importance of education. They sought to bring about taxpayer funding for public schools. These men believed that teachers should earn more than the private market had so far allowed.

The teachers allied themselves politically with the Whig tariff men who also wanted to get money by means of government that they couldn't get from the private market. The political success of the Whigs would improve the teachers' chances of obtaining their public school system. It was in the pecuniary interest of the teachers, then, to help promote the political success of the Whig tariff men. It was useful for the Whigs to have the teachers in their coalition. Not only did they add their numbers, but teachers could indoctrinate their students in the Whig version of "republican citizenship." This was political "log-rolling." It was useful and convenient for both groups because the political opponents of the one group were usually opponents of the other.

Just as Maylin and Wattles joined in the Whig anti-slavery crusade, so did also Horace Mann and Henry Barnard. They were both political Whigs and New England's leading advocates for school "reform." Following the earlier example of Calvin Stowe who was also a member of the "College of Teachers, Mann also traveled to Prussia to view their educational system. Like Stowe before him, Mann published a widely distributed report of his visit and his recommendation that the Prussian system of compulsory public education be adopted. Generally revered by teachers and historians as the "Father of the Common School Movement," Mann was elected to replace the deceased John Quincy Adams in the U.S. House of Representatives where he carried on the Whig tradition of anti-slavery agitation.

Many agriculturists who objected to protective tariffs because of their depressing effect on farm commodity prices also objected to tax supported mandatory public school systems. The study of such things as ancient Greek literature was not something that was useful coaxing wheat, oats and barley from the fertile Ohio soil. Nor was it helpful in growing cotton in the South where there was also substantial opposition to taxpayer-financed public schools.

Semmes' father-in-law, Reverend Oliver M. Spencer, Sr., was one of the leading innovators in providing access to education for the children of Cincinnati. He was one of the founders and financial benefactors of the Cincinnati Lancasterian Seminary in 1815. He himself drafted the original articles for governance of the institution. His name is cited in the Ohio law authorizing the incorporation of the school.

The school utilized Joseph Lancaster's "monitorial method" by which older students (the "monitors") tutored hundreds of younger students under the supervision of one teacher. Because of its detailed organization and marvelous efficiency, the system was widely used with great success in the United States and abroad in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Cincinnati school charged its students a tuition of $8 per year. The Presbyterian Church granted a 99-year lease for the building site, asking only that it have the right to designate up to 28 poor students as "charity scholars".

Because of Spencer's intimate involvement in Cincinnati education, it is likely he understood exactly the objectives of teachers Maylin and Wattles in joining the Whig political anti-slavery agitation. As tax legislation opened the spigots of government money flowing to education, the economical private-market compromises of the Lancasterian system were no longer necessary. Semmes undoubtedly learned much of this at the Spencer dinner table while he was litigating with the anti-slavery men. There was probably no better man in Cincinnati to instruct him in these matters than his own father-in-law.

Fanning Mills

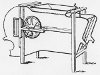

John Melendy was a manufacturer of fanning mills, or winnowing machines as the British called them. These devices were commonly used on farms for separating wheat (in Britain, "corn") from chaff and dirt by means of an air blast propelled by rotating fan blades mounted on an iron axle turned by a crank and gears. Sieves shaken by cranks separated grains from smaller and larger foreign matter by size. James Melendy was a partner in the business. Peter Melendy, although associated in the business with John and James Melendy, was also an investor in Merino sheep (wool being an object of tariff protection).

The manufacture of the mechanical components was protected by the tariff on iron. The winnowing machines were in common use in Britain and where they benefited from the lower cost of the iron from which the mechanical components were made. Improvements in the design were frequently being made in Britain. Consequently, the British were in a good position to dominate the market in the United States in the absence of high tariff barriers.

The Watchmaker

Gamaliel Bailey, Sr., was a silversmith and watchmaker. In the 1830s, foreign manufacturers, particularly the Swiss, were the dominant suppliers of the American watch market. Before the end of the eighteenth century, the Swiss learned to divide the labor of watchmaking into many different operations. The jobs were parceled out in large numbers to those who specialized in the various operations. They had become skilled at manufacturing the small, specialized machinery for efficiently making watch components.

By 1835, the Swiss were exporting watches by the hundreds of thousands. They exported large numbers of watch movements as well as finished watches. Many American watchmakers bought Swiss watch movements and installed them in their own watch cases. But they were unable to compete in manufacturing the whole watch for the mass market. American watch manufacturing did not succeed to a large extent until well after mid-century when the Waltham manufacturing came into successful operation with tariff protection.

Early in the century the Swiss had devastated the British watchmaking industry. The British manufacturers complained they were hobbled by successive license fees and taxes imposed on the raw materials and the various operations in watchmaking.

The son, Gamaliel Bailey, Jr., was hired by Lewis Tappan to edit The Philanthropist in Cincinnati and years later The National Era in Washington, D. C. In this latter position, Bailey became later became the acknowledged "immediate founder" of the Republican Party by his editorial hectoring of the protectionists to abandon their old parties and coalesce into the new Republican Party.

Rees E. Price was a brick maker. The construction of the manufacturing facilities in Cincinnati required bricks by the millions. Price had become wealthy on the new construction. As long as Cincinnati manufacturing was prosperous and growing, Price was certain to be prosperous. A reduction in the tariff would retard the growth of manufacturing in Cincinnati. Price's investment in brick-making facilities required a continuing stream of new growth in manufacturing to give a return on the investment. Such a man would be highly sensitive to reduced tariff rates. A lull in the expansion of manufacturing would nearly stop his business completely.

The following table summarizes the tariff interests of the members of the executive committee of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.

| Ohio Anti-Slavery Society Executive Committee | |

|---|---|

| Name | Tariff Interest |

| James C. Ludlow | Carriage parts and manufacturing real estate |

| Isaac Colby | Sons are tailors of ready-made clothing |

| Wm. Donaldson | Tailor in ready-made clothing industry |

| James G. Birney | Hired by Lewis Tappan to edit the Philanthropist anti-slavery newspaper |

| Thos. Maylin | English teacher, propagandist for common schools |

| John Melendy | Fanning mill manufacturer |

| C. Donaldson | Cutlery supplier to ready-made clothing industry |

| Gamal. Bailey | Watch manufacturing |

| Rees E. Price | Brick maker for factory construction |

| Augustus Wattles | Clergyman, teacher, activist for common schools, American Anti-Slavery Society agent hired by Lewis Tappan |

| William Holyoke | Carriage components manufacturing. |

There were eleven members of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society executive committee. Of these, eight had obvious interests in tariff protected manufacturing. Two (Ludlow, Holyoke) had interests in the manufacture of carriage components. Three (Colby, Wm. Donaldson, C. Donaldson) had interests in the clothing industry. One, Bailey, Sr., was a watchmaker, one, Melendy, was a fanning mill manufacturer and the remaining man, Price, manufactured bricks for factory construction.

Of the remaining three, two were hired by Lewis Tappan, the nation's leading pro-tariff organizer. Birney was the hired editor for The Philanthropist. Wattles was a young clergyman hired as an agent of Lewis Tappan's American Anti-Slavery Society to preach the anti-slavery message and solicit contributions for the cause.

Two of the men, Maylin and Wattles, were members of the public education propaganda organization that was closely allied with the tariff men. Their political agenda was closely linked with that of the tariff men.

Without exception, then, the members of the anti-slavery society executive committee had a significant pecuniary interest in the political success of the Whig tariff party.

There was nothing frivolous about the work of the anti-slavery committee. They were deadly in earnest. The businesses that supplied their daily bread had expanded under tariff protection. Now their wealth depended upon its maintenance. If tariff protection were diminished, production and sales of Cincinnati manufacturing would likely suffer significantly as foreign manufactured products came flooding into Cincinnati. They faced a very real prospect of serious financial setbacks and possible bankruptcy. The Slave Power had brought about the scheduled reduction in the protective tariff. It was indeed the mortal enemy of their now tariff-dependent business. The members sought to do what they could to bring about the limitation of southern political power.

The structure of this committee was similar to the structure of the American Anti-Slavery Society, the New York Anti-Slavery Society, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and others. It consisted of a few businessmen with tariff interests and their youthful hired editors and clergyman-agents.

These were the circumstances that gave Semmes a close, personal view of the abolitionists and their motives. Although Semmes did not report all of these details, in view of the Spencer family connections in Cincinnati, Semmes was undoubtedly aware of these facts.

Return to Active Duty in the Navy

Semmes was promoted to lieutenant and called to active duty to serve aboard the U.S.S. Constellation. Afterwards he was assigned to survey the Mississippi Sound for preparation of naval charts. In 1841, he purchased land in Baldwin County, Alabama, on the west bank of the Perdido River, between Mobile and Pensacola, Florida. He moved his family there from Cincinnati. He was ever thereafter a citizen of Alabama.

During the Mexican War, he served on board the Raritan in support of the invasion at Vera Cruz on the eastern coast of Mexico and on land with the U.S. Army under General Winfield Scott as it moved the two hundred miles west to capture Mexico City. After the war, he returned to Alabama and published a popular account of the war, Service Afloat and Ashore during the Mexican War. The book still serves as a respected source of historical information about the war.

Semmes was appointed lighthouse inspector for the Gulf of Mexico and later made Naval Secretary of the Lighthouse Board in Washington. There he served under Admiral William B. Shubrick, the Board chairman.

After South Carolina seceded from the Union, Semmes advised President Buchanan's new Treasury Secretary, Philip F. Thomas, that he would not recommend that the coast of South Carolina "be lighted against her will."

For the next few weeks, he performed his routine duties at the Light-House Board, "but," as he described it, "listening with an aching ear and beating heart, for the first sounds of the great disruption which is at hand." On February 14, 1861, while he was sitting quietly at home with his family, a messenger brought him the fateful telegram.

Called to Serve the Confederate States

Montgomery, Feb. 14, 1861.

Sir:--On behalf of the Committee on Naval Affairs, I beg leave to request that you will repair to this place, at your earliest convenience

C. M. Conrad, Chairman.

Commander Raphael Semmes, Washington, D. C.

Charles Magill Conrad, a lawyer from New Orleans, had represented Louisiana in the U.S. Congress and had served as U.S. Secretary of War under President Millard Fillmore. He now represented his state in the Confederate Congress where he attended to naval affairs. He knew Semmes could be a valuable asset to the Confederate navy.

The next day, on February 15, 1861, Semmes resigned his U.S. Navy commission and made plans to travel south to serve the Confederate States navy. Now, he had to break up his comfortable household, take his children out of school and send them with his wife back to her family.

He traveled by train to Montgomery, Alabama, to meet first with Mr. Conrad. He went to the state capital where the Confederate Congress was in session. He was recognized and admitted to the floor where he saw many familiar faces. Next, he called on Confederate President Jefferson Davis who asked him, pointedly, whether he had resigned his U.S. Navy commission. He assured Davis that his allegiance now belonged to the new southern government. That settled, the two men sat down to discuss woefully unprepared state of Confederate military affairs. There was no navy yet, so Davis proposed to send Semmes north to gather materials of war and men skilled in the art of manufacturing them.

Semmes traveled north, stopping in Virginia, then in Washington, D.C. where inauguration preparations were underway. While he was there, Abraham Lincoln arrived in Washington on the night train from Philadelphia. Semmes left Washington for the North where he toured the workshops of New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts, making purchases and supply contracts. Although northern manufacturers were willing to sell to him, many of the contracts could not be fulfilled because the war came too quickly the next month. He returned to Montgomery where he was put in charge of the Lighthouse Bureau, a position he occupied until he put to sea.

In Command of the Sumter

In April 1861, Semmes traveled to New Orleans to accept command of the CSS Sumter, a converted merchant steamer with bark-rigged sails and 473 tons displacement. He installed additional coal carrying capacity and five large cannon. On June 30, when the blockading Union warship steamed away from its station at the mouth of the Mississippi River to "chase a sail," the Sumter slipped out of the river and into the Gulf of Mexico. For six months, she raided Union merchant shipping, all the while eluding Union warships bent on her capture.

In August, she put in at Port-of-Spain, a British-controlled port on the western coast of Trinidad, to make some repairs to her rigging and take on some more coal. Her main yard had broken in collision with another ship. Carpenters on shore made another one and fitted it to the ship.

The British governor of Trinidad, Robert W. Keate, was uneasy at his first visit by a Confederate States warship. His orders were to preserve British neutrality. He was concerned about the possible interruption Trinidad's trade with the northern U.S. states. "A great deal of trade goes on between Trinidad and the northern ports of North America," he reported to the British Secretary of State for the Colonies Henry Pelham-Clinton, "and Captain Semmes, I imagine, has not failed to take this opportunity of obtaining information with regard to the vessels employed under the flag of the United States in this traffic."

"Fears are entertained," he said, "with regard to one or two now expected." "It is to be hoped that the presence of the Sumter in these waters will soon be made generally known, and that, while the civil war continues, the lumber and provision trade, any interruption of which would cause serious embarrassment to this community, will be carried on in British bottoms."

Semmes Explained to Captain Hillyar that the Tariff Caused the War.

of Penny Lees.jpg)

Governor Keate sent a message to Captain Hillyar of Her Majesty's ship Cadmus that was patrolling nearby, asking him to come and investigate. About to enter the harbor at Grenada, Captain Hillyar learned of the message, turned his ship and steamed the one-hundred miles to Port-of-Spain. The Cadmus was a British Royal Navy steamer, a 21-gun warship of 2216 tons displacement and a crew of 270. She was well equipped to assert any necessary authority.

After the Cadmus came into port, Commander Semmes sent one of his lieutenants to call on her captain. It was the first foreign ship of war to which he had extended the courtesy of a visit. The men of the Sumter were cordially received and the officers of the Cadmus returned the visit. The British lieutenant examined the Sumter captain's credentials and saw that she was indeed a duly commissioned Confederate States man-of-war, not a privateer or pirate.

The next morning, the captain of the Cadmus, Henry S. Hillyar, came aboard the Sumter for a visit. Hillyar was a member of a distinguished British navy family. His grandfather had been a naval surgeon. His father was Admiral Sir James Hillyar. On the British warship Phoebe, James Hillyar sailed in 1813 to disrupt the United States fur trade in the Pacific. Discovering that the Essex, an 864-ton U.S. frigate, was preying on British shipping, he set out to capture her. At Valpraiso, after a fierce gun battle in which the Phoebe's longer range 18-pound guns devastated the Essex, Captain David Porter surrendered his ship to Captain Hillyar. David G. Farragut, who years later led the U.S. Navy fleet to capture New Orleans in 1862, was a midshipman serving in that battle on board the Essex.

Semmes had "a long and pleasant conversation on American affairs" with Captain Hillyar, who had brought with him a recent New York newspaper.

"I must confess," said Hillyar, as he handed the newspaper to Semmes, "that your American war puzzles me - it cannot possibly last long."

"You are probably mistaken, as to its duration," replied Semmes. "I fear it will be long and bloody. As to its being a puzzle, it should puzzle every honest man. If our late co-partners had practiced toward us the most common rules of honesty, we should not have quarreled with them; but we are only defending ourselves against robbers, with knives at our throats."

"You surprise me," said Captain Hillyar; "how is that?"

"Simply," said Semmes, "that the machinery of the Federal Government, under which we have lived, and which was designed for the common benefit, has been made the means of despoiling the South, to enrich the North." "[T]he workings of the iniquitous tariffs," explained Semmes, "under the operation of which the South had, in effect, been reduced to a dependent colonial condition, almost as abject, as that of the Roman provinces, under their proconsuls; the only difference being, that smooth-faced hypocrisy had been added to robbery, inasmuch as we had been plundered under the forms of law."

"All this is new to me, I assure you," replied Captain Hillyar. "I thought that your war had arisen out of the slavery question."

"That is a common mistake of foreigners," explained Semmes. "The enemy has taken pains to impress foreign nations with this false view of the case." "With the exception of a few honest zealots," he said, "the canting, hypocritical Yankee cares as little for our slaves, as he does for our draught animals. The war which he has been making upon slavery, for the last forty years, is only an interlude, or by-play, to help on the main action of the drama, which is Empire; and it is a curious coincidence, that it was commenced about the time the North began to rob the South, by means of its tariffs."

"When a burglar designs to enter a dwelling, for the purpose of robbery," Semmes explained by analogy, "he provides himself with the necessary implements. The slavery question was one of the implements employed, to help on the robbery of the South. It strengthened the Northern party, and enabled them to get their tariffs through Congress; and when, at length, the South, driven to the wall, turned, as even the crushed worm will turn, it was cunningly perceived by the Northern men, that 'No Slavery' would be a popular war-cry, and hence they used it."

"It is true," said Semmes, "we are defending our slave property, but we are defending it no more than any other species of our property - it is all endangered, under a general system of robbery." "We are, in fact, fighting for independence. Our forefathers made a great mistake, when they warmed the Puritan serpent in their bosom; and we, their descendants, are endeavoring to remedy it."

Captain Hillyar bid farewell and returned to the Cadmus. As soon as he left, the Sumter sailed out of Port-of-Spain, loaded with fresh provisions from the rich tropical island, to continue her career preying on Yankee shipping. The next day, Captain Hillyar wrote a report to his superior officer, Admiral Alexander Milne, about the encounter.

He had little confidence in the Sumter's sturdiness for battle. "She mounts 5 Guns between decks, Viz. 4 heavy 32 pns and one Pivot 68, but having been a passenger boat her scantling [structural timber] is so light (not more than 5 or 6 inches) that I don't think she could stand any firing, and the guns being only from 4 to 5 feet from the water, could not be worked in bad weather."

"She broke the blockade at New Orleans and was nearly captured," he reported. "Since then she has been most successful, having captured eleven prizes, two she sank and the rest are at St. Iago-de-Cuba under the protection of the government with the sanction of the Governor in Chief until they receive orders from Spain as to the matter."

"I called on Captain Semmes next morning as he was getting his steam up," said Hillyar, "and he gave me full assurance that he would in no way interfere with British or Neutral Trade, but complained greatly at the Southerners having no Port to send their Prizes to, and that he would be obliged to destroy all he took in consequence of the strict blockade on the South Ports, and the Stringent Proclamation of all the Great Powers. He thinks himself safe at Cuba as the Government of Spain's Proclamation is only against Privateers and their Prizes and says nothing about Men of War."

"She sailed yesterday under Steam at 1 P.M.," wrote Hillyar, "and from the Signal Station was reported going to windward and from his questions I should fancy he is going to cruise for some of the California and China homeward bound ships, and there is no doubt he will do an enormous amount of damage before he is taken, for he seems a bold determined man and well up to his work." Hillyar's report to Admiral Milne was strictly naval business and did not report any of his conversation with Semmes concerning American tariff politics.

The fact that such a man as Captain Hillyar was unaware of the role of the tariff in causing the war is not surprising in view of the role of the major city newspapers in failing to report it. The New York Times and the New York Tribune were both Republican political organs. Editors of both newspapers were intimately involved in the founding of the Republican Party. Protective tariffs were their religion. They were not about to admit the pernicious side effects of the tariffs on the South.

The next January, while at Gibraltar for an overhaul, Union ships found the Sumter and blockaded the port. Semmes dismantled the armament and sold the ship at an auction in the port. He and his crew traveled overland to escape the blockade. Semmes took command of the C.S.S Alabama at Madeira and embarked on a highly successful two-year career disrupting Yankee merchant shipping. By the end of that career, Semmes had captured many more enemy merchant ships than any other naval commander in maritime history.

Semmes' description of the slavery question as "one of the implements employed, to help on the robbery of the South" was precisely correct. The slavery issue was a tool employed solely for its efficacy in shifting the balance of representation in Congress for purpose of gaining northern control of federal taxation and appropriations.

Semmes' assignment of the tariff as cause was not simply a lame excuse for secession hauled out in a post-war guilty attempt at justification of slavery. Long before the Civil War, Semmes had a deep appreciation for the fundamentals of political economy and, in particular, of the pernicious effects of protective tariffs on the various sectors of a nation's economy.

Ample evidence of this is found in Semmes' report of his experiences in the Mexican War, published a full decade before the U.S. Civil War began. It is worthwhile to examine in detail what Semmes said then, not only to show his knowledge of tariff effects, but also to show that his understanding of political economy was the foundation for a sense of right and wrong that drew him to the southern cause in the first place. Semmes' comments on Mexican industry demonstrate that he was no mere military tourist, but rather he was a perceptive observer of the pernicious effects of the Mexican tariffs.

Semmes' Observations on Mexican Manufacturing and Political Economy

After the successful U.S. invasion at Vera Cruz on the eastern coast of Mexico, Semmes traveled to Jalapa (Xalapa), a city in Eastern Mexico about one-hundred-forty miles east of Mexico City, to meet with General Winfield Scott on a mission to obtain the release by the Mexicans of a war prisoner. While at Jalapa, Semmes visited several factories there, particularly several large ones manufacturing cotton goods.

"These, and other establishments of the kind," he wrote, "have been built up by an excessive tariff of protection, amounting in fact to an exclusion of all foreign competition." As an example of all the rest, he described the Joseph Welsh & Co. factory. Welsh was an Englishman who had represented England as vice-consul in Mexico who also saw industrial opportunity.

The stone factory buildings were, he said, "in good style, and form a pleasing feature in the landscape." "The main building was commodiously arranged, and well ventilated with a profusion of windows, each one of which looked out upon a landscape that might have fired the imagination of a painter. The lower story was devoted to sixty looms, while two thousand spindles were run in the upper, or second story." Most of the factory operatives, he said, were Indian females. "They were neat and cleanly in their persons, had the look of health, and were, some of them, quite fair and pretty."

"Labor is cheap, food is abundant," he said, "and with equal advantages as to the price of the raw material, these Mexican factories might compete with our own in the production of coarse cotton goods." "[B]ut such is the want of energy in the planter, in raising the raw material, and so completely is all foreign competition excluded," he said, "that the few cotton lords who have built up establishments of this kind, put a price three and four-fold greater on their goods, than similar fabrics can be purchased for in the United States."

"There is a rivalry, in Mexico," he explained, "between the planters and manufacturers, on the subject of protection; the elections of members of congress, in particular districts, turn on this point; and the consequence is, that both interests are protected." "The government, therefore, is guilty of the absurdity," he said, "first, of excluding the foreign manufactured goods, in order that similar fabrics may be produced at home; and secondly, of rendering it impossible that these should be produced, by withholding a supply of the raw material -the Mexican cotton crop never equaling the demand, and sometimes falling short by a third or a half. A beautiful illustration of the system of protection!"

After his arrival in Jalapa, General Scott's chief quarter-master, Captain Irwin, invited Semmes to reside with them in the large stone custom-house. The house was, said Semmes, "an establishment for the collection of certain duties of transit, levied on all foreign goods, in addition to the alcabalas [a sales tax, originally 10% in Spain] already paid at the maritime custom-house, where they had been first entered." It was yet another burden on foreign commerce, dragging the country's economy down.

Moving west with the army, Semmes came to the industrial city of Puebla, located about 135 miles west of Vera Cruz in a broad, fertile valley in central Mexico. "In the suburbs of the city we passed through one of the seven garitas, or internal custom-house gates, that serve, in Puebla, as elsewhere in Mexico, to harass and destroy the inland commerce of the country."

"Puebla," he wrote, "still maintains its superiority, as a manufacturing district, over the rest of the republic. Its temperate climate, enjoyed by means of its elevation, its abundant agricultural supplies, and the best of water-power in every direction, give it every facility for becoming the great workshop of Mexico. Its chief products now, as in the days of the prosperity of Cholula, are cotton yam, and cotton cloth; both of which it produces of very good quality." "In the whole of Mexico," Semmes reports, "there were in operation in 1844, 117,531 spindles-being an increase on the year before, of 10,823-and 2609 looms. Of these, Puebla possessed 38,094 spindles, and five hundred and thirty looms."

"This branch of manufacturing industry," he wrote, "has received great impetus within the last few years, the legislature extending to it, as has been before remarked, a degree of protection, amounting to an absolute prohibition of foreign competition."

In Mexico, Semmes thought however, there might be a mitigation of the severe effects on trade. "This mode of fostering and building up a particular branch of industry, at the expense, in the beginning, of other interests, is," he said, "perhaps, less objectionable in Mexico than in other states, from the nature and configuration of the country." "There are," he explained, "no large rivers to afford facilities for commerce. Canals and railroads to connect the tablelands with the sea-coast, are, to a greater or less extent, impracticable; and hence, an entire stagnation of the agricultural interest must ensue, unless the superfluous hands employed in this branch of industry be withdrawn, and established in manufacturing and other pursuits, so as to counteract, at the same time, the tendency to over-production, and to ensure an inland market to the farmer and grazier. Mexico, for the want of facilities for transportation, exports nothing of bulk; and unless, therefore, she can consume her agricultural products herself, her surpluses will rot on the hands of the producers. Not only will this be so, but in the midst of abundance, the indigence of large numbers who will be incapable of finding employment, must necessarily ensue."

A decade earlier, on August 22, 1837, the administration of Mexican President General Anastasio Bustamante had already awarded a railroad concession to Francis Arrillaga, a businessman in Vera Cruz. Arrillaga was given the right to construct a railroad from Vera Cruz to Mexico City, the country's capital, exactly the connection that Semmes was lamenting did not exist. The terms of the grant required the builders to construct a branch to Puebla and complete the whole railway in twelve years. In 1842, under the administration of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, the railroad from Veracruz was started, but in seven years only seven miles of rail were built.

Because the tariff effectively prohibited imports, however, exports were also crippled, so there was little point in constructing the road to transport bulk export commodities to the seaport.

Because the taxes stifled the economy, business languished and the people were unemployed and politically angry. There was almost constant civil war in these years as the liberales who supported a decentralized federal form of government struggled against the more authoritarian conservadores who preferred a stronger, more centralized government. The stunted economy and political strife were not fertile soil for the growth of a railroad.

Under later administrations, especially that of Benito Juarez, rail was laid at a faster rate. Finally in 1873, the line from Mexico City to Veracruz was completed. The completed railway is shown in the 1877 map.

Under later administrations, especially that of Benito Juarez, rail was laid at a faster rate. Finally in 1873, the line from Mexico City to Veracruz was completed. The completed railway is shown in the 1877 map.

Under the prohibition of tariff protection, manufactories proliferated in Mexico, but with an unfortunate side effect. The growth in manufactories, as Semmes noted, "outstripped the capacity of the country to supply them with the raw material."

Cotton, he observed, was "produced principally in the four states of Vera Cruz, Oaxaca, Jalisco, and Michoacan (in the tierras calientes [hot lands]), and the crops have hitherto been anything but encouraging. In 1844, the entire crop amounted to but two millions of pounds, or six hundred and sixty bales! Four-fifths of that quantity was produced in Vera Cruz and Oaxaca; the crops having failed entirely in the states of Jalisco and Michoacan."

These crop failures were not, as Semmes put it, "an unusual accident." "[T]he early and drenching rains, the worm, and high winds," he said, "frequently prove destructive to the hopes of the planter." He described an example from the prefecture of Acapulco. In that year, he said, "there were planted 3850 bushels of seed, and the total yield was only 447,- 600 pounds of seed cotton, which, at six cents per pound-its value in the market-was worth $26,850. The cost of cultivation amounted to the sum of $146,400!"

The discouraged cotton planters, he reported, were "talking of abandoning its culture altogether in this region, and of removing to states farther north, as to Durango and Coahuila; where, from experiments partially made, there seems to be more hope of success." Those states, thought Semmes, "resemble more nearly, in their climate and physical peculiarities, the cotton-growing states of our Union, and the plant may, no doubt, be domesticated here, to a greater or less extent. "Mexico," he thought, "will have great difficulties to encounter, in her efforts to build up a manufacturing system of her own in this important branch. She will have of necessity to depend, for a series of years to come, if not indefinitely, upon a foreign supply of the raw material.

Semmes saw clearly the advantages to Mexico if she were to permit free trade. "If she were to throw open her ports to the free admission of the article," he thought, "we could supply her with it cheaper, perhaps, than she will ever be able to produce it; and although this would interfere somewhat with her system of being her own producer as well as consumer, it would nevertheless give a great impetus to her industry, and redound much to the national prosperity." "But, unfortunately," Semmes lamented, "her policy is hampered with antagonistic interests, and the cotton planter, as well as the manufacturer, demands protection."

Semmes recognized the problem of "equality" of rights to tariff protection. If one, the manufacturer, should be entitled to have it, why not the other, the planter, also? "It is not denied that he ought, equally with the manufacturer, to have this," Semmes acknowledged, "but the amount of the protection has been, and still is, the great bone of contention between them. The manufacturers are willing to adopt a sort of sliding-scale, by which the price may be kept up to twenty-four cents per pound, but the planters complain that this would not enable them to realize a sufficient profit; and they have hitherto carried their point, to the great injury of the manufacturing interest"

Semmes described the manufacture of woolen goods, which he noted, were necessary at all seasons of the year on higher altitudes of the great plains of Mexico. The tablelands of the Cordilleras and the highlands of the northern states of Mexico, Semmes believed were "eminently adapted to the growing of wool; and Mexico will," he thought," no doubt, if she persevere, excel in this department of manufacture."

"Silk," he said, "is manufactured to a considerable extent in Michoacan, in the city of Mexico, and in Puebla, but it requires also, the protection of the government."

Semmes visited the porcelain manufactories in Puebla. They produced some "very creditable wares," he thought. That industry, he said, requires no protection from the government." Semmes recognized that the Puebla area had another export product another great possibility for export-potash. It was abundant on the plain of Puebla and near the lakes of Mexico City. "The earth is saturated with it," he said "and it can be extracted and sold at about one-fifth the price of the potash of the United States."

Semmes described the large paper manufacturing industry recently established at Puebla. The company wanted to manufacture other kinds of paper, but a sufficient supply of the right kinds of rags were not available in the country. He noticed the scarcity of rags as raw material and thought they could be imported to advantage because the paupers who supplied rags would not be able to muster the political strength to get legislation excluding foreign rags.

One particular item of Mexican manufacture was hard to miss. It was saddles. "One is struck," said Semmes, "with the great quantity of saddles manufactured everywhere in Mexico. Indeed, all the world travels on horseback in this country; on mountain and plain alike, and in proportion to the universality of the practice,' are the skill and ingenuity required in the adornment of the animal." "Every one," he said, "who mounts a horse at all, mounts him en caballero-as a cavalier-and be he gentle or plebeian, he must have a certain amount of finery for his steed."

Semmes told of seeing a saddle being finished in one of the shops. The saddler told him that it would cost eight hundred dollars. It was not, said Semmes, "by any means an unusual price." "Stirrups of massive silver," he said, "are frequently used, and jewels and ornaments of gold are not at all uncommon."

Semmes did not remark on it in the book, but leather and saddle manufacturers in the United States were leaders in demanding tariff protection and in the antislavery crusade against the South that opposed it.

Semmes Fully Understood That The Tariff Caused the War

In view of Semmes' legal work in defending the anti-abolitionist mob members against Lewis Tappan's antislavery minions in Cincinnati, his demonstrated understanding of political economy in his book on the Mexican War and his record of great competence as a naval commander, his testimony concerning the cause of the conflict must be heard and accorded substantial weight.