In 1819, in the midst of intense frustration over the defeat of tariff legislation by slave-state senators in Congress, Hezekiah Niles embarked on an anti-slavery crusade in the pages of his newspaper, the Niles' Weekly Register.

On May 8, Niles published an article, "The Mitigation of Slavery, No. 1," the first of a numbered series of articles on the slavery question. In earlier years, mentions of slavery in the pages of the Register were relatively scarce. Now they became frequent.

He set out five propositions that he would address in this and succeeding articles. The third proposition had a particular bearing on the tariff. He would limit the westward spread of slavery.

3. On the proper means of checking the propagation of the slave-species—Among others, by narrowing the extent of country in which they shall be permitted to exist, with a notice of the late debates, &c. in congress about allowing the introduction of slavery into the regions west of the Mississippi.

This third proposition would not make anyone a slave who was not already a slave or free any existing slave. It's sole purpose was political. It would limit the political power of the southern agricultural states to obstruct the tariff legislation that Niles' desperately wanted.

The tone of the article was, on its surface, that of an even-handed, objective examination of the subject. The "knowing ones," that is, the tariff men who understood the political balance, recognized it as the political banner behind which they should form their column.

On the same page of the paper, in the very next article , "Hints on Domestic Manufactures," Niles reminded his readers of the necessity of the tariff protection that the slave owners had opposed.

Every intelligent man now sees, and many begin to feel the necessity of applying the surplus labor of the people of the United States, to furnish commodities for their own wants. We cannot much longer, be "buyers of [foreign] bargains," because we cannot pay for them. There is also an increased spirit of patriotism among us, to encourage all sorts of domestic manufactures. The balance of trade has long been against us, and nothing prevented us from being as "hewers of wood" to the manufacturers of Great Britain, but the great productiveness of our country, and the extraordinary prices which our agricultural commodities brought in foreign parts, aided by the genius and enterprize of our citizens in commercial pursuits. But the means of keeping that balance within reasonable bounds no longer exist—-there is so little demand for our products, that a saving voyage is now accounted a good one, by our merchants.

The country was sinking into a financial recession, "The Panic of 1819." European demand for foodstuffs was declining as her men returned to their farms after the wars. The Second Bank of the United States had contracted credit. Ever cheaper British manufactures were flooding into the country. Times were hard.

Niles deprecated the ideal of free trade.

"The freedom of trade" is a pretty thing to talk about—it looks well upon paper; but exists only in imagination, or by making slaves of one nation to pamper another.

He turned his attention to the arguments of the slave owners.

The idea has been entertained by some of our agriculturalists, that a duty laid upon foreign manufactures operated as a tax levied upon them, without any countervailing advantage. There never was a more silly notion than this.

So it was that Niles dismissed as a "silly notion" the southerners' complaint that high tariffs were financially damaging to agricultural interests.

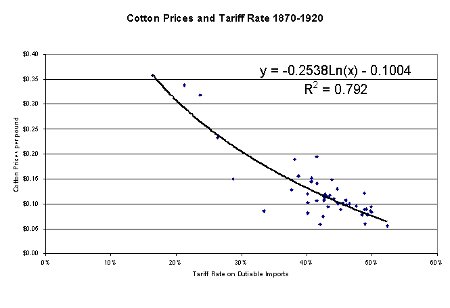

As the following chart reminds us, high tariffs devastate southern agricultural revenues.

It was not just a "silly notion." It was real economic disaster, but Niles could not see it. He preferred to believe in a system by which northern manufacturers used government as a tool to interfere with someone else's commerce in order to benefit their own. He was unable to understand the fundamental immorality of that system.

Niles was the victim, as were many others, of the delusive fantasy that high taxes and trade restrictions came without heavy costs to anyone in the country.

Niles briefly asserted that the foreign demand was "of no comparison with the demand of the home market" as a further justification for protection. But, as he explained, it needed no further repetition.

But we have said enough on these subjects, and demonstrated the facts so often, that we shall simply refer to them now. However, let any notions be entertained that may, we have arrived to that point in our affairs, when it is the home market which must be depended upon.

Niles had long been agitating for the imposition of protective tariffs. He would continue to do so for the better part of the next two decades.

These two articles were the great turning point. It was Niles' embarkation on the great anti-slavery propaganda crusade. Niles took up the advocacy of slavery restriction as a means to get the tariff he wanted. Here he began to educate his following in the North on the evils of slavery and the desirability of restricting its westward migration. He educated the tariff men that southern objections to tariff protection were a "silly notion." The reader can view both articles in their entirety here.

As the editor of the nation's most influential newspaper, he was in an awesome position of power to sway the public to his cause. In this he must be regarded as one of the most important causing agents of the U. S. Civil War.

When Niles was done with his career, Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune took up the torch of anti-slavery and tariff protection. He, in turn, was joined by Henry Jarvis Raymond, founder of the New York Times and one of the founders of the Republican political party.

Through most of the nineteenth century, these leading papers deprecated southern resistance to the tariff as a silly notion while advocating the limitation of slavery as a means to get the balance of power to control the tariff. They eventually got it. It resulted in tragedy far beyond the U.S. Civil War.